Bringing aviation in line with the Paris agreement: Will flying save the forests?

Last week was a big week for climate policy. Last Tuesday the countries of the EU ratified the Paris agreement, taking it past the required threshold to becoming law – which it will on 4 November. On Thursday the 191 countries of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) finally agreed a deal on curbing emissions from international aviation. International aviation and shipping have steadfastly been excluded from all previous climate agreements, so such a deal has been a long time coming.

Aviation currently accounts for around 2% of global CO2 emissions (slightly more than the UK). So why all the fuss?

Firstly, aviation is growing at roughly 5% a year, when most other sectors have sluggish growth. Secondly, the sector is hard to decarbonise. Together these mean that aviation emissions could use up to a quarter of the remaining carbon budget that can be emitted if we are to keep global warming below 1.5 C.

So what does this deal do? The deal effectively caps CO2 emissions at 2020 levels by using market based measures to offset any global emission growth beyond 2020 levels. Voluntary stages until 2026 are replaced by a compulsory stage from 2027-2035.

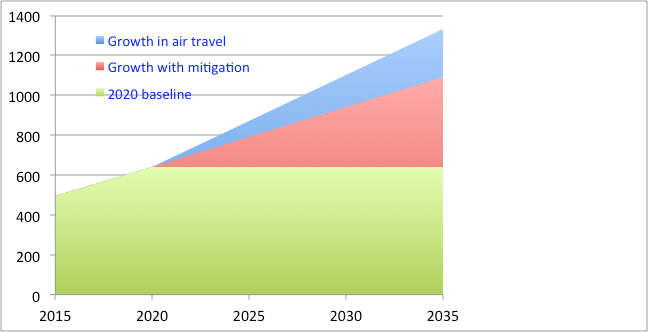

Even though the first stages are voluntary – all the major nations that airlines fly to and from have agreed to take part – airlines are expected to be able to mitigate around two fifths of the annual growth by replacing airframes and engines with more fuel-efficient models as well as employing better air traffic management and efficient ground operations. Using biofuels instead of kerosene may also slightly reduce emission growth. These measures will still leave around three-fifths of growth that will need to be managed by the Carbon Offset and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA – see Figure 1).

Figure 1: global aviation emissions of CO2 (million tonnes per year). The red triangle is the amount of offsetting required

At first airlines will offset a proportion of global growth according to their size but by the end of the period airlines will be individually responsible for their own growth. The deal is expected to add around $10 to the cost of long haul tickets and $2-3 for short haul fares, reducing the profitability of the industry by about 1%.

Two important criticisms of the deal are that it only seeks to curb growth in emissions rather than cut them. And it is cuts are needed to meet the Paris targets. The deal also does not account for other emissions of aviation (especially contrails) which also warm the climate. However, its credibility will really hinge on if the offsetting schemes are effective.

The detail of how the offsetting will work is the next stage of negotiation which should be finalised by 2018. It is expected to follow closely how offsets are treated in the Paris agreement (paragraphs 20-25 of the agreement). Offsets will begin with Clean Development Mechanism projects set up under the Kyoto Protocol.

It is likely that forest protection and restoration projects will also be allowed. Protecting and restoring forests has been extensively proven as able to provide genuine carbon offsetting opportunities as well as co-benefits to indigenous communities and biodiversity under REDD+. For example, work by Priestley International Centre for Climate’s Dominick Spracklen has highlighted the carbon sequestration potential of mountain forests. Tropical deforestation is the major cause of global biodiversity loss and accounts for substantially more carbon dioxide emissions than aviation. Carbon offsets from aviation could provide a sustained and sizeable funding source to reduce carbon emissions from tropical deforestation and may be one of the last chances we have to save remaining tropical biodiversity.

While progress on the mitigation of aviation emissions is welcomed, especially for the co-benefits for forests, offsetting as a mechanism for reducing the industry’s impact on the climate remains controversial. Further research is needed to understand how it can be made to really deliver the very substantial reductions in greenhouse gases necessary as a warming world rapidly ups the stakes.

Piers Forster and Dominick Spracklen