Huge permafrost thaw can be limited by ambitious climate change targets

Global warming will thaw about 20% more permafrost than previously thought, scientists have warned; potentially releasing significant amounts of greenhouse gases into the Earth’s atmosphere. A new international research study, including climate change experts from the University of Leeds, University of Exeter and the Met Office, reveals that permafrost is more sensitive to the effects of global warming than previously thought.

The study, published in Nature Climate Change, suggests that nearly four million square kilometres of frozen soil – an area larger than India – could be lost for every additional degree of global warming experienced.

Permafrost is frozen soil that has been at a temperature of below 0ºC for at least two years. Large quantities of carbon are stored in organic matter trapped in the icy permafrost soils. When permafrost thaws the organic matter starts to decompose, releasing greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane which increase global temperatures.

It is estimated that there is more carbon contained in the frozen permafrost than is currently in the atmosphere.

Thawing permafrost has potentially damaging consequences, not just for greenhouse gas emissions, but also the stability of buildings located in high-latitude cities.

Roughly 35 million people live in the permafrost zone, with three cities built on continuous permafrost along with many smaller communities. A widespread thaw could cause the ground to become unstable, putting roads and buildings at risk of collapse.

Recent studies have shown that the Arctic is warming at around twice the rate as the rest of the world, with permafrost already starting to thaw across large areas.

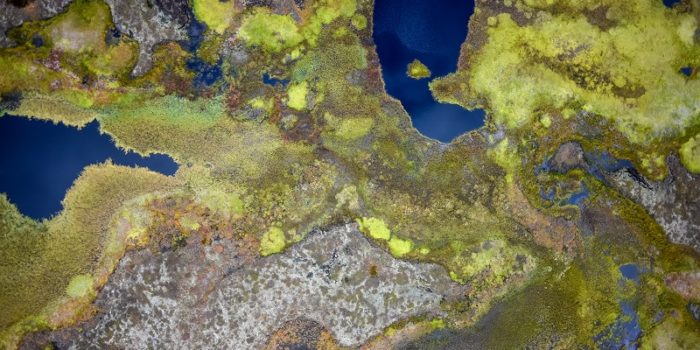

Thawing permafrost peat plateaus in northern Norway. Image: Sebastian Westermann

The researchers, from Leeds, Exeter, Sweden, Norway and the Met Office, suggest that the huge permafrost losses could be averted if ambitious global climate targets are met.

Dr Sarah Chadburn led the research project whilst based at the School of Earth and Environment at Leeds. She said: “A lower stabilisation target of 1.5ºC would save approximately two million square kilometres of permafrost.

"Achieving the ambitious Paris Agreement climate targets could limit permafrost loss. For the first time we have calculated how much could be saved.”

In the study, researchers used a novel combination of global climate models and observed data to deliver a robust estimate of the global loss of permafrost under climate change.

The team looked at the way that permafrost changes across the landscape, and how this is related to the air temperature. They then considered possible increases in air temperature in the future, and converted these to a permafrost distribution map using their observation-based relationship.

This allowed them to calculate the amount of permafrost that would be lost under proposed climate stabilisation targets.

As co-author Professor Peter Cox of the University of Exeter explained: “We found that the current pattern of permafrost reveals the sensitivity of permafrost to global warming.”

The study suggests that permafrost is more susceptible to global warming that previously thought, as stabilising the climate at 2ºC above pre-industrial levels would lead to thawing of more than 40% of today’s permafrost areas.

Co-author Dr Eleanor Burke, from the Met Office Hadley Centre, said: “The advantage of our approach is that permafrost loss can be estimated for any policy-relevant global warming scenario.

“The ability to more accurately assess permafrost loss can hopefully feed into a greater understanding of the impact of global warming and potentially inform global warming policy.”

Further information

Image credit: Permafrost pattern, Wikimedia Commons

Since completing the research project, Dr Chadburn has now moved to the University of Exeter.