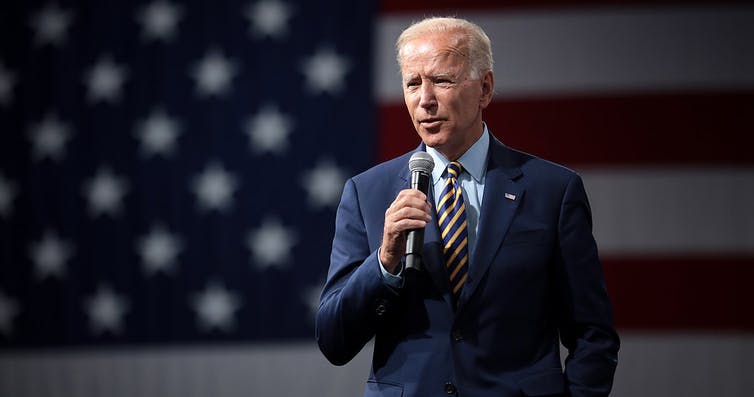

Joe Biden's Earth Day summit – what could it achieve for action on climate change?

A blog from Professor Richard Beardsworth, Head of the School of Politics and International Studies

To mark the first Earth Day on April 22 1970, the then US president, Richard Nixon, planted a tree on the White House lawn. More than five decades later, a much greater task falls to the current occupant of the Oval Office.

Joe Biden has invited 40 world leaders to take part in a two-day virtual gathering that will commence on April 22. With just over six months before countries meet in Glasgow for the UN’s annual climate summit, Biden will be hoping to tease more radical commitments for reducing emissions from his guests and give international negotiations a shot in the arm.

The stakes, as ever, are high. Despite a brief reprieve during the lockdowns in 2020, global carbon emissions are set to come roaring back in 2021 to near their pre-pandemic peak.

So what is the most that can come from the Earth Day summit? And how will we know if it was a success?

What’s the point of a summit before COP26?

After four years of the US being effectively absent from climate negotiations, Biden’s summit is clearing the ground for countries to reach stronger targets at the UN’s Conference of the Parties in November 2021, also known as COP26. The summit is meant to send a message that the US is not only back in the Paris Agreement, but keen to be back at the helm leading international efforts.

An agreement between the then US president Barack Obama and China’s president Xi Jinping in late 2014 broke the political deadlock between developed and developing countries following the diplomatic failure of COP15 in Copenhagen. Their bilateral agreement set the stage for global consensus in 2015, at COP21 in Paris, when all countries agreed to nationally determined contributions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in line with limiting global temperature rise to 2°C (updated to 1.5°C in 2018).

On his recent visit to China, the special presidential envoy for climate, John Kerry, spoke with the country’s chief climate negotiator, Xie Zhenhua. By meeting Zhenhua prior to the renewal of the Paris Agreement, Kerry and the Biden administration are showing the world that a similar breakthrough is possible at COP26, through cooperation between its two biggest greenhouse gas emitters.

Despite their deep antagonism on issues such as trade and human rights, cooperation between the US and China is intended to set a strong example to other countries in the run up to COP26, particularly the next largest emitters who have yet to set more ambitious targets for reducing emissions.

What might a good outcome from the summit look like?

The first good outcome arrived early. Following pressure from scientists and environmental groups, Biden committed the US to a 2030 target of reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 50% compared to 2005 levels on the eve of the summit – more than twice as ambitious as Obama’s target of 20% in 2014.

Following the terms of the recent agreement between Kerry and Zhenhua, the US might coax Jinping to publicly confirm his pledge of September 2020 that China will achieve carbon neutrality “before 2060” and reach “peak carbon emissions by 2030”.

Another good outcome from the summit would be for the US and Chinese leadership to cooperate on measures to achieve their updated targets during the next few years. The next largest emitters, India and Russia, could choose to follow suit and submit updated targets for the next decade.

Finally, the countries with the lowest emissions which have been invited to the summit, including Bangladesh and an array of small island states, could gain a more concrete sense of the resources that bigger emitters are willing to commit to help them adapt to climate change. The four outcomes, together, would certainly help pave the way for COP26 to achieve its climate ambition in the autumn.

What are the obstacles to that?

Leading by example can backfire. Much has happened in international and domestic politics since 2014. Many countries will be wary of diplomatic moves by the US in the short term. After all, what happens to these promises after the 2022 Congressional elections when Republicans may regain Congress? Several countries from the Global South will have plenty of their own reasons to be suspicious of the US in a global leadership role.

Past resistance to the ambitions of the US (as at COP15) could reemerge despite the increasing threat of climate catastrophe, reversing the virtuous circle of diplomatic peer rivalry among states. This summit constitutes a leap of faith on the part of its host and an ambivalent wager on the part of its guests. The summit will decide the direction of that wager.

Which are the countries to watch and why?

There are four sets of countries to watch during the summit.

First, the US and China – their ambition will hopefully spur the next biggest emitters, the EU, India and Russia. The response of the last two will be particularly interesting – will they agree to hop on the bandwagon? Third, countries such as Australia, Canada, Japan and South Korea, which all have a stake in the climate leadership of the US due to the nature of their relationships with China, but have not yet updated their targets.

Finally, those countries most vulnerable to the near-term effects of climate change, such as Bangladesh, Jamaica and Kenya. Will they sign off on any of the summit’s supposed achievements?

What can Biden’s first three months tell us about his climate plan?

The Biden administration’s approach – his cabinet appointments overall, the stimulus packages, the cross-departmental consultations – is serious, comprehensive and integrated. As I and a colleague recently suggested, the US president’s international commitments to climate are critical to the success of his domestic transition. That’s another major reason for holding this summit now.![]()

More information

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Main image: Jlhervàs/Flickr, CC BY-SA